Once upon a time in the East: Adventures in the French Foreign Legion

Recollections of a legionnaire during the ‘pacification‘ of Vietnam after the Tonkin War of 1883–1885. A reconnaissance by a small party towards a village where rebel activity is suspected. an excellent and unusual scenario for a skirmish wargame.

Richard Bird

2/20/20246 min read

Background to war

The Sino-French War, also known as the Tonkin War, unfolded from August 1884 to April 1885 without a formal declaration of war. This limited conflict witnessed remarkable performances by Chinese forces, achieving notable successes on land despite ultimately conceding victory to the French. While French forces triumphed in most engagements, the Chinese compelled a hasty French withdrawal from Lạng Sơn in the war's later stages.

The complexities of the conflict, influenced by factors such as foreign support, naval dynamics, and regional threats, led to China entering negotiations. The outcome resulted in China ceding its influence in northern Vietnam to France and recognizing French treaties with Annam, solidified through the Treaty of Tientsin. Despite achieving strategic objectives, France faced domestic repercussions, contributing to the downfall of Prime Minister Jules Ferry's government. This historical episode not only shaped the balance of power in East Asia but also had significant political ramifications for both nations involved.

In 1889, the notorious Luu-Ky successfully abducted three French colonists, Rocque and Baptiste Costa, during a shooting expedition near Haïphong. The captives endured over two months of mistreatment and privations at the hands of the band. They were eventually released upon payment of $80,000.

Inspired by their compatriots' success, Chinese soldiers from Kwang-si and Kwang-tung frontiers abandoned their uniforms, infiltrating Lang-son and Cao-Bang provinces. They conducted raids, burning villages, seizing cattle, slaughtering men, and capturing women.

Meanwhile, in Yen-Thé, supporters of Ham-Nghi, secretly backed by Hué mandarins, rebelled. Led by De-Nam, a former military mandarin, they occupied fortified positions, possessing ample arms and ammunition. The rebels received support from wealthy villages in the Upper Delta, sympathizing with their cause. This tumultuous situation characterized the state of Tonquin in April 1891.

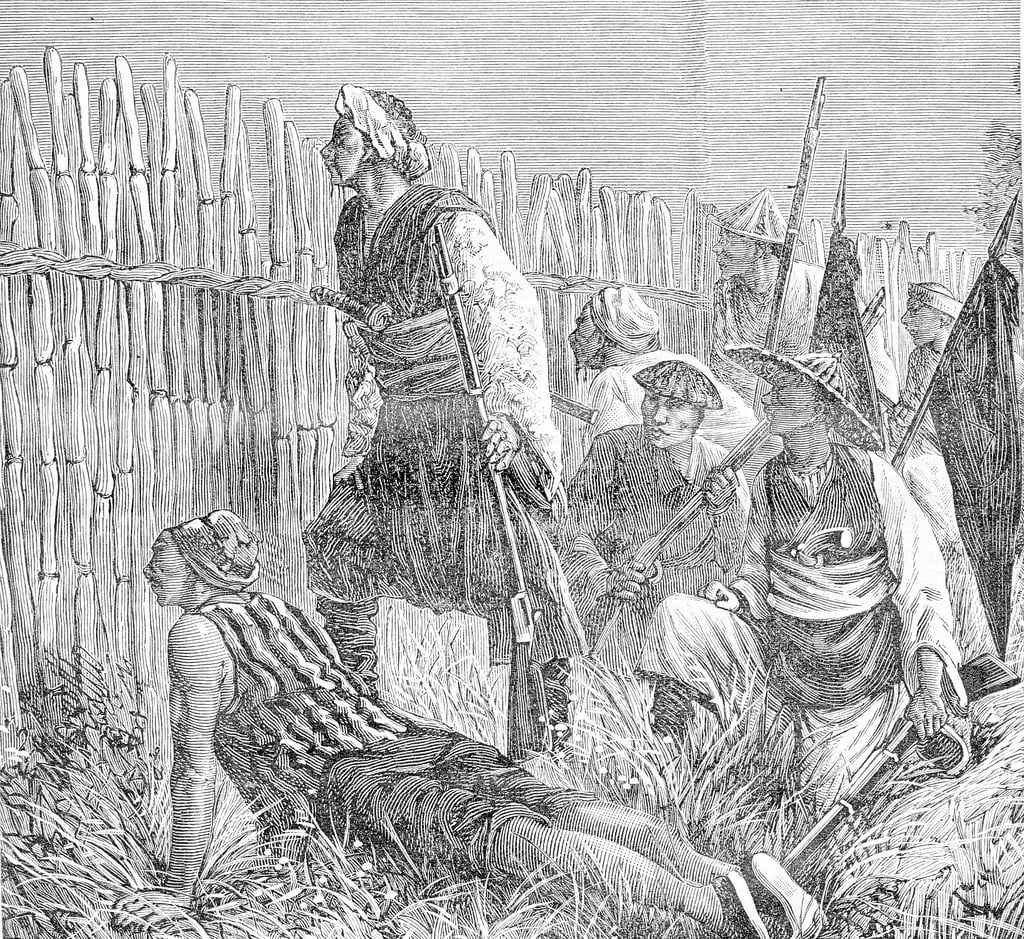

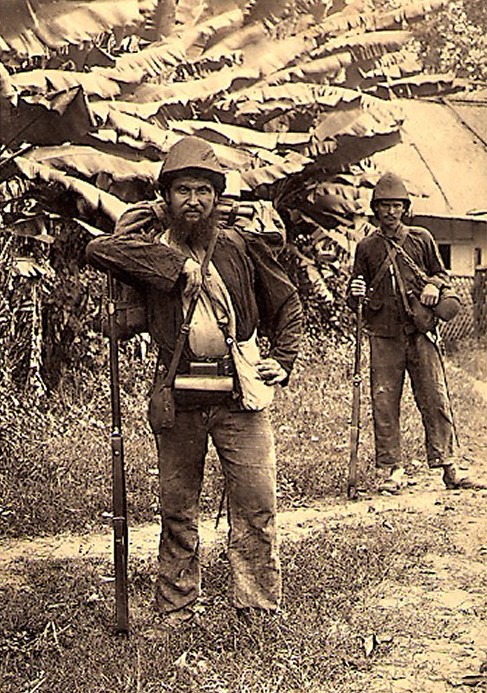

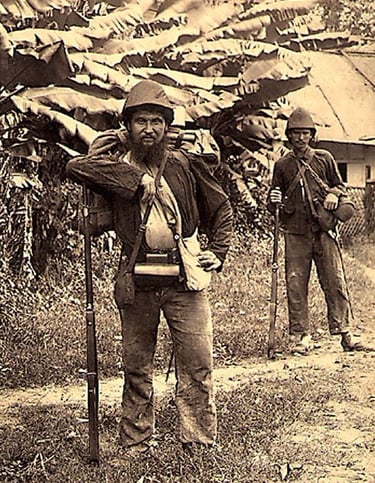

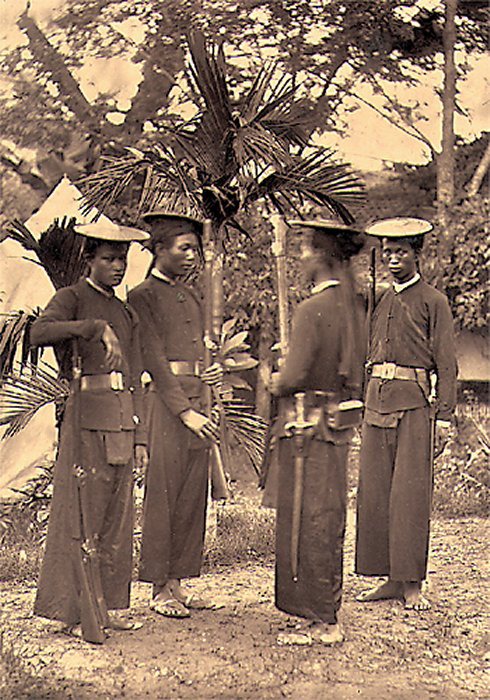

Rebels preparing to defend their village against the dastardly French

In order we have an illustrations of a marine infantryman and of a legionnaire. Lastly a photograph of legionnaires on campaign.

Illustrations by Maurice Rollet and photo by Dr. Charles Hocquard.

A wargame scenario from actual events in 1891

I have in my possession memoirs from an individual in the French Foreign Legion. Apart from his early days in the Legion, much of this writing concerns his adventures and recollections of the French pacification of region after the Tonkin War. As an amateur historian and wargamer, I was triggered into researching more of this fascinating conflict of French colonialisation, which sowed the seeds for a much larger and dominant anti-colonial movement towards the end of World War Two, led by Ho Chi Minh.

This article is the first of what might be a short series of incidents involving our true-life hero. The following is a description of events while he was on a reconnaissance mission led by the intrepid Captain Plessier.

An eventful reconnaissance to Long-Thuong

Due to the military authorities possessing accurate intelligence regarding the rebels' strength and positions, the Brigade issued orders for periodic reconnaissance missions into the districts north of our fort. The goal was to explore the region and gather topographical sketches for a reliable map, aiding the officers in the forthcoming large-scale winter campaign mandated by the government. I participated in the initial expedition on September 12th, which aimed to assess the accessibility of the track to Long-Thuong, an insurgent village untouched since January, and determine if it was still inhabited and fortified.

Setting out from Nha-Nam at three in the afternoon, our detachment, consisting of thirty Legionaries and an equal number of tirailleurs, was not intended for a direct confrontation with the enemy. To alleviate the oppressive heat, we carried only the six ammunition packets in our belt pouches—36 rounds. Fortunately, the tirailleurs accompanying us were better equipped, with 120 rounds per man.

Approaching within a quarter of a mile of our destination, about a league and a half north of our position, we encountered no incidents. The fields were lush with cultivation, and as we neared, the female reapers hastily fled towards the hamlet, their cries echoing in the air. Under Captain Plessier's orders, we deviated from the path, extended our formation, and advanced across the cultivated ground towards the village. A small reserve, commanded by Lieutenant Bennet, remained on track.

Approximately 200 yards from the hamlet, we faced intense gunfire from a robust enemy contingent within the village. Taking cover behind the embankments that separated the fields, we engaged in a firefight. However, a severe crossfire from the left flank resulted in casualties: one tirailleur was killed, two others were wounded, and one Legionary was wounded.

Engaged in this skirmish were some of De-Nam's regulars, summoned from their entrenched positions in the forest by village inhabitants using long, copper-speaking trumpets. The eerie bellowing of these trumpets resounded above the rifle reports and commands.

Our reserve extended on the left but failed to contain the enemy, and skirmishers advanced at regular intervals, firing at us. As our ammunition dwindled, the situation became precarious, prompting the distribution of cartridges from the fallen and native infantrymen. The need to restrict native troops to volley-firing arose due to their reckless ammunition expenditure.

Witnessing Captain Plessier under fire for the first time, I observed his calm and collected demeanor. Dressed in a white drill suit, he remained exposed without taking cover, walking confidently behind the line. Despite being a target, his presence inspired confidence among the men. As the action continued, the order to retreat by echelons was given, having accomplished the reconnaissance objective. Continuing the engagement would have been a breach of military strategy and an invitation to disaster.

The Tonkinese Rifles, established in 1884, were Tonkinese light infantrymen supporting the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps during the Sino-French War. Led by French officers, they engaged in conflicts against the Chinese and participated in expeditions against Vietnamese insurgents during the French Pacification of Tonkin. Up until World War I, the Tonkinese Rifle regiments wore uniforms resembling indigenous dress, including a bamboo headdress, red sashes, and loose-fitting tunics. During this period, the uniforms evolved to align with the standard khaki drill of the French Colonial Infantry, losing their distinctive indigenous features.

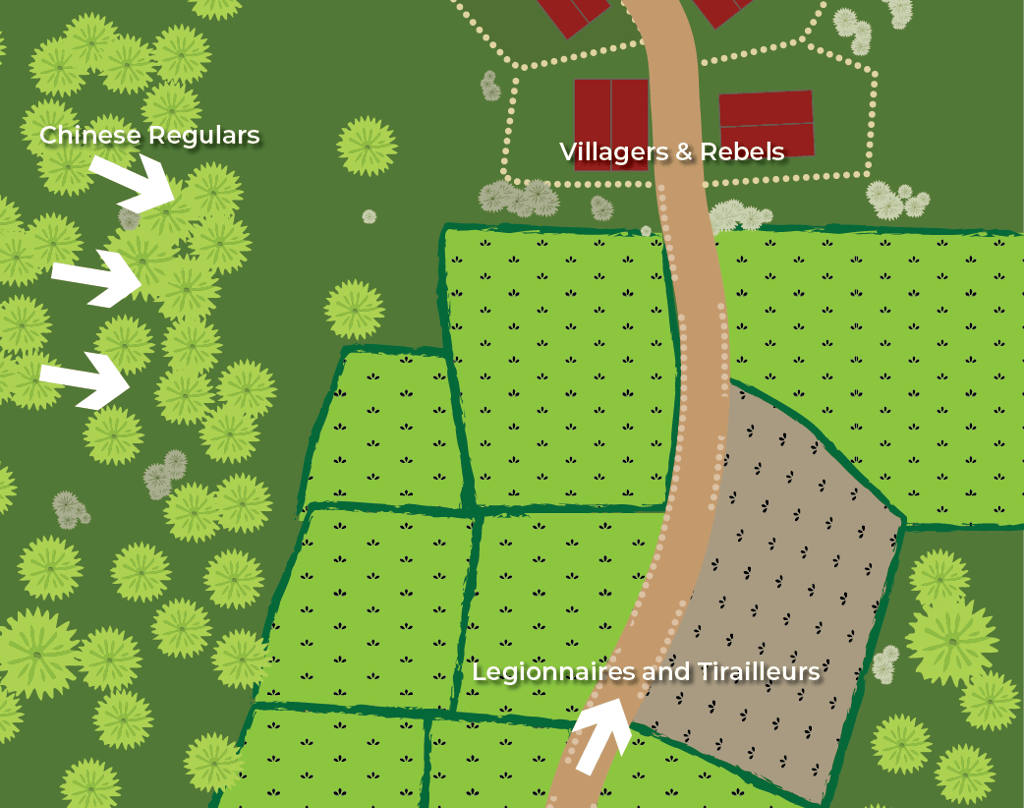

Wargaming the fight

I feel that this small scenario lends itself to particular skirmish wargame rules. The Men Who Would Be Kings and Sharpe Practice come immediately to mind. We have a ready-made hero, Captain Plessier, ably assisted by Lieutenant Bennet. Most of the troops would have been armed with the 1874 Gras rifle. initially, but it was replaced by the 1886 Lebel Model in May 1891.

There were an equal number of Legionnaires and Tirailleurs. For the rebels, I’d suggest 40 Chinese regulars and 60 rebels.

The Chinese regulars would most likely be armed with single-shot breechloaders, such as Sniders and bolt-action M1871 Mausers. The rebel contingent in the village would have mixed weapons, perhaps even old matchlocks, and then there were the proverbial bamboo spears.

The French have to survive for 8 turns but need to satisfy a successful recce by having an officer within 6 inches of the village for one turn. Captain Plessier must survive. Having done so, they can retire to the starting position on the track without losing 20%. The Chinese regulars can arrive on the table on the D6 throw, but not on the first turn. Oh..and no civilian casualties, apart from rebels.

For figures, there is a wonderful range on exactly this war from the Gringo 40s. Figures from their Taiping range would be ideal too You can get a bargain copy of ‘Imperial Chinese Armies, 1840–1911' from eBay and ‘French Foreign Legion, 1872–1914’, and likewise from this link.